Text in Memoriam of Zhu Qiqian

In the middle of a desert inhabited only by shamanic presences, what meets the eye, like a mirage, is a Folly, a name that stands not only for that which has always eluded psychic habitation and rational control- the real reason for a fear of Kamchatka- but also for certain enchanting maisons de plaisance, pavilions devoted to idleness and pleasure. … little by little, the successive waves of nomads who made their camps in it, there grew around that folly the essence of that which was to appear since then under the name of literature

-Roberto Calasso

The city was born in a frenzy of crime: under the drizzle of 1930, a hopeless year, Zhu Qiqian raised a ceremonial silver shovel and bludgeoned the city wall. No longer defending the self from the outside: the crack in the wall would let in the cold breeze, the rushing blue water. The arm raised with a silver, sharpened tool: this gesture would be repeated again and again in the decades to come, as the organs of the body rose in revolt, ruining the elegant and statuesque structure of old Beijing. The city would be attacked from inside and out, a chained Gulliver whose individual components began to assault it, turning the city into a rubbled warzone, streets filled with luscious young ladies scurrying through trash-laden corridors. Beijing, the scene of the crime: the motive, to preserve the life of the people. In a world of rational and symmetrical orderings, what is human is always assumed to be criminal, regarded with suspicion.

Rheumy eyed grandfathers walk past, slowly, endlessly. Their destination is at the same time unknown and obvious (for in this entire city, there is not a single habitation which is not a dusty, lonely room). The ends of the earth: the discarded ends of cucumbers, parched in appearance; under shading trees, shirtless men eat peanuts, gabbling and grunting. Sunbeams trickle through alleys scattered with trash. This place may appear to have been carelessly assembled; that is because it was intended as a temporary settlement, intended to be glimpsed through the trees as a rest-point, a stop-point, a place to drink and leave empty bottles and the charred ashes of the bonfire. Various outsiders, taking for granted that the objective of human life is to stop in place and start accumulating objects, placed to one’s right and to one’s left, in front of and behind one, objects which should be readily comparable to those objects of the others (and thus, easy to assess what one’s position is, relative to these others); they came to this place and, sighing at its disorderly hubbub, decided to organize things. “This may not be a city, just a collection of huts; still, it’s better than nothing.” A worldview completely opposed to that of those of us whose objective is to spend life shedding objects, finally arriving at a state of divine purity, naked, grubby, skin peeling, stubbled chin, but unburdened by memories of the past, unaware of the possibility of the future. The metropolis: the accumulation of the toils of past generations made large stone slabs, thickets of wire and concrete, a tawdry replacement for the grand green forests we once walked through. In fact, the metropolis is a memento mori: every grey surface, every dingy stall selling wine and cigarettes, recollects to us our unfreedom, our compulsion to continuously spend our time articulating economic rhythms, those rhythms which take precedence even over our own biology, and which absolutely leave no room for the unknown. Everything must be known; everything must be knowable.

The nomadic tradition of the North of China; warlike. The Chinese city, ruptured at the commencement point between market and wall; well, down south they just have markets. Here, we have walls, enclosing nothing, enclosing ourselves, built by slaves, built by ourselves; and since Zhu Qiqian raised his shovel, even the walls are gone, transformed into ring roads, endless circulation, the No-Stop City, but one with awful traffic jams. In this largest and soon most powerful city of the world, where every small lane is endlessly grimy, where “bare life” assumes a literal sense: these urbanites are not wearing clothes, their children’s genitals are visible, they sit gnawing, suspiciously gazing at passerbys. These lanes emerged as a compromise: their name, the Mongolian word for town (a word which in the Mongolian language should properly be considered a curse). This, this is where the endless life on horseback tottered to an end. In these sunlit pavilions, under these weeping willows, lies the urban geography of a mass (once known as ‘horde’) reconfigured as an economy; and it is unclear to any of us exactly what should be done next. Wander from room to room? Eat cherries and cucumbers, sticks of barbecued lamb? Observe the glinting silence of the black lake? Pass by shuttered palaces, shuddering? Yes: this city where many activities suggest themselves, unsculpted by economy, activities flagrantly random and sacrificial: there are no straight lines here, only wanderings and wanderers. From one place to another, and back again: how ridiculous these commutes seem when their routes are described by the cracking voices of the Northern plain. A northern plain which extends from metropolis, from ring roads and circles, from a maddening frenzy of movement, all the way through to the silent woods, in which deer and gazelles twirl through sunlight. Or, in another season, where icicles mercilessly accumulate, gripping down the eaves of the houses, forcing them into obeisance.

Yes, and here, humans do not seek to wrest themselves out of reality like oysters ripped naked from rocks: instead, the urge is to glide, to cruise, to feel wind whispering through one’s hair, to find the body of the other and swirl down a dark red spiral into intoxicated exhaustion. To integrate oneself into the world: or to discover that, thanks to the urges of the body, one has never left.

In my apartment, I also arranged objects around me, but ones which interested me more than the typical ones: various agricultural commodities, a few books. I swept long, black hairs up every day- I threw them into the trash. Criminal, beast, lord: synonyms; I found myself collapsing between these three categories, like a drunk man falling through the paper-screen walls of a Japanese restaurant.

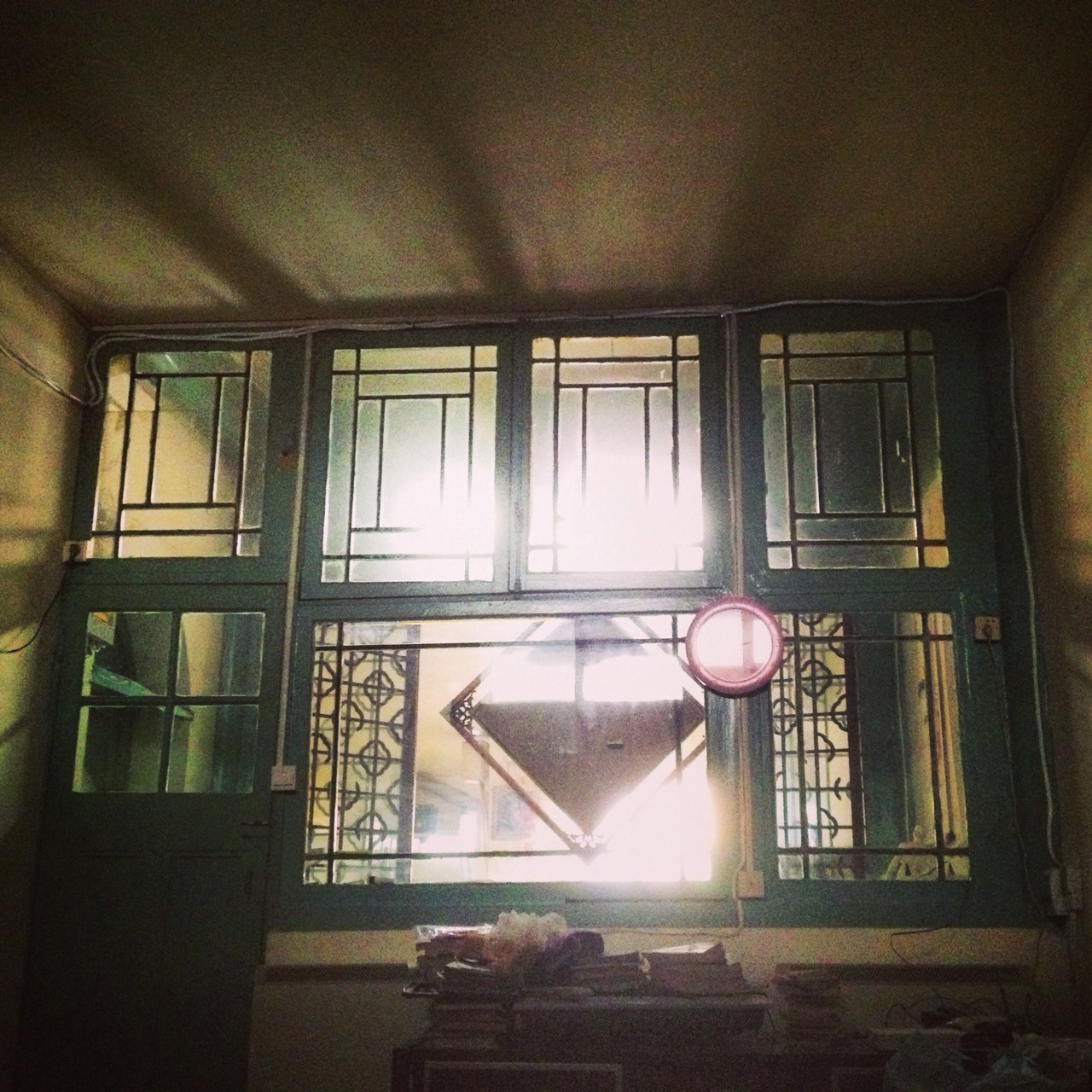

Here, nothing quivers: well, you quivered. Go back to sleep. Meanwhile, nothing else quivers. The feeling of one’s own animality is as strong as a powerful drug; blinking, stretching, body smeared (as always) with salt. This is a pure land. Yes, in the empty, blank room where I watched you sleep, I discovered a purity beyond any which I have ever known.